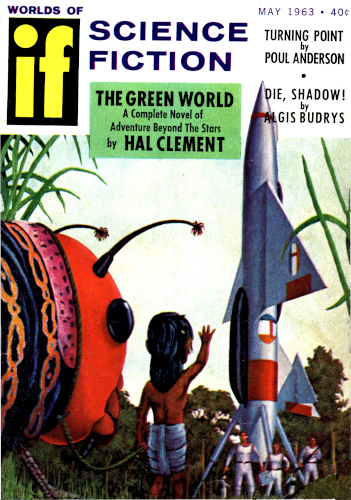

ANOTHER EARTH

BY DAVID EVANS & AL LANDAU

Whatever it was that had happened in the

test, it badly needed a good explanation.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, May 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I

Lieutenant Colonel Philip Snow, Flight Surgeon, USAF, and Test Directorof the Aero-Medical Laboratory, was pacing the study floor in hisquarters, asking himself for the dozenth time in the past half-hour:What had happened to Richardson during the test that afternoon?

He was no stranger to problems. He had been living with them for thepast few years, and they had been problems the like of which had neverbefore challenged the ingenuity of man. For he was the head of a smallcommunity of men, scientists like himself—medical specialists of allkinds, psychologists, electronic technicians, physicists, pressureengineers, mathematicians and so on, each one of them an acknowledgedexpert in his particular field—who had worked together with one endin view: to send a man into space and bring him back safely to Earthagain. To put it more excitingly: to enable man to take his first steptoward the conquest of the universe.

The result of their labors to date was the Capsule, a bottle-shapedcontraption which occupied the center of the laboratory floor.

It wasn't very big; just big enough to contain a man enclosed in aspacesuit, lying on a couch surrounded by instruments. But there wasn'ta square inch of the capsule itself, the spacesuit, and the instrumentswhich hadn't presented innumerable problems, the solving of which hadbeen the result of endless research and theorizing and testing.

And in the same way, and almost to the same extent, there wasn't asquare inch of the man, too, which didn't present problems, all ofwhich must be solved before he could be sent into space.

And so, in test after test, one of the chosen astronauts had lain onthe couch in the capsule, wired through his spacesuit to the dozens ofdials and graph recorders on the consoles at which sat the watchingspecialists. It seemed there was nothing that could happen inside hisbody that they could not know about. They could read every flexingof his muscles, every heartbeat, every tiny shifting of temperature,every reaction of his blood and of his complicated nervous system. Onthe encephalograph, they could even detect reactions in the mass ofgray matter which was his brain, any sign of tension there, and aboveall, any symptom of that strange phenomenon of which so little was yetknown, and which was called the "breakoff"—the eerie sensation ofcomplete isolation from Earth, the trancelike apathy and indifferenceto survival that can attack not only high-flying pilots, but deep-seadivers, "the rapture of the depths," and sometimes it was accompaniedby hallucinations in which strange forms and sounds were seen and heard.

In the case of Lieutenant Hamilton Richardson, USN, there had beenno mysterious troubles of this kind—in fact, no troubles of anykind at all. Aged thirty-six, he had been one of the first of theastronauts to volunteer. He had passed with flying colors every oneof the grueling preliminary tests, mental and physical, and as far ascould be judged by science, he had seemed to be the perfect specimen,mentally and physically, for the job. In the many tests made with himinside the capsule, nothing had gone wrong with him. There had beenno signs of fatigue or