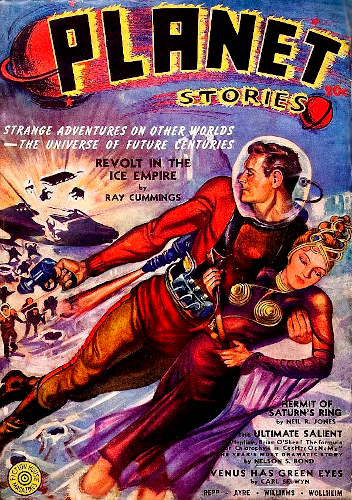

THE ULTIMATE SALIENT

By NELSON S. BOND

Brian O'Shea, man of the Future, here is

your story. Read it carefully, soldier

yet unborn, for upon it,—and upon you—will

one day rest the fate of all Mankind.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Fall 1940.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

He glanced at me slowly, and a bit sadly, I thought. "I'm sorry,Clinton," he said, "but that won't do. It won't do at all. It will haveto be written. You see—you won't be here then...."

I thought at first he was the census-snoop, returning to poke hisproboscis into whatever few stray facts he might have overlooked thefirst time. My wife was out, and when I saw him coming up the walk,that bulky folder under his arm, I answered the door myself—somethingI seldom do—sensing a sort of reluctant duty toward the minions ofUncle Sam.

He was a neat and quiet person. One of those drab, utterly commonplacemen who defy description. Neither young nor old, tall nor short, stoutnor slender. He had only one outstanding characteristic. An eagerintensity, a piercingness of gaze that made you feel, somehow, as ifhis ice-blue eyes stared ever into strange and fathomless depths.

He said, "Mr. Clinton?" and I nodded. "Eben Clinton?" he asked. Then,a trifle breathlessly I thought, "Mr. Clinton, I have here somethingthat I know will prove of the greatest interest to you—"

I got it then. I shook my head. "Sorry, pal. But we don't need some." Istarted to close the door.

"I—I beg your pardon?" he stammered. "Some?"

"Shoelaces," I told him firmly, "patent can-openers or fancy soaps.Weather-vanes, life insurance or magazines." I grinned at him. "I don'tread the damned things, buddy, I just write for them."

And again I tried to do things to the door. But he beat me to it.There was apology in the way he shrugged his way into the house, butdetermination in his eyes.

"I know," he said. "That is, I didn't know until I read this,but—" He touched the brown envelope, concluded lamely, "it—it's amanuscript—"

Well, that's one of the headaches of being a story-teller. Strangethings creep out of the cracks and crevices—most of them bringing withthem the Great American Novel. It was spring in Roanoke, and springfever had claimed me as a victim. I didn't feel like working, anyway.No, not even in my garden. Especially in the turnip patch. Hank Cleaverisn't the only guy who has trouble with his turnips.

I sighed and led the way into my work-room. I said, "Okay, friend.Let's have a look at the masterpiece...."

His first words, after we had settled into comfortable chairs, mademe feel like a dope. I suppose I'm a sort of stuffed shirt, anyway,suffering from a bad case of expansion of the hatband. And I'd beentreating my visitor as if he were some peculiar type of bipedal worm.It took all the wind out of my sails when he said, by way of preamble,"If I may introduce myself, Mr. Clinton, I'm Dr. Edgar Winslow of thePsychology Department of—"

He mentioned one of our oldest and most influential Southernuniversities. I said, "Omigawd!" and broke into an orgy of apologies.But he didn't seem to be listening to me; he was preoccupied with hisown explanation.

"I came to you," he said, "because I understand you write storiesof—er—pseudo-science?"

I winced.

"Science-fiction," I corrected him. "There's quite a difference, youknow."