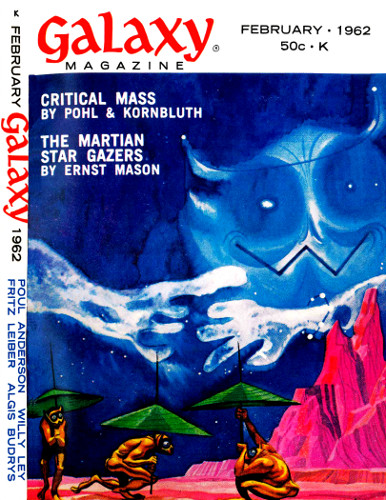

THE BIG ENGINE

By FRITZ LEIBER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine February 1962.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Have you found out about the Big

Engine? It's all around us, you

know—can't you hear it even now?

There are all sorts of screwy theories (the Professor said) of whatmakes the wheels of the world go round. There's a boy in Chicago whothinks we're all of us just the thoughts of a green cat; when the greencat dies we'll all puff to nothing like smoke. There's a man in thewest who thinks all women are witches and run the world by conjuremagic. There's a man in the east who believes all rich people belong toa secret society that's a lot tighter and tougher than the Mafia andthat has a monopoly of power-secrets and pleasure-secrets other peopledon't dream exist.

Me, I think the wheels of the world just go. I decided that fortyyears ago and I've never since seen or heard or read anything to makeme change my mind.

I was a stoker on a lake boat then (the Professor continued, delicatelysipping smoke from his long thin cigarette). I was as stupid as theymake them, but I liked to think. Whenever I'd get a chance I'd go toone of the big libraries and make them get me all sorts of books.That was how guys started calling me the Professor. I'd get books onphilosophy, metaphysics, science, even religion. I'd read them and tryto figure out the world. What was it all about, anyway? Why was I here?What was the point in the whole business of getting born and workingand dying? What was the use of it? Why'd it have to go on and on?

And why'd it have to be so complicated?

Why all the building and tearing down? Why'd there have to be cities,with crowded streets and horse cars and cable cars and electric carsand big open-work steel boxes built to the sky to be hung with stoneand wood—my closest friend got killed falling off one of those steelboxkites. Shouldn't there be some simpler way of doing it all? Why didthings have to be so mixed up that a man like myself couldn't have asingle clear decent thought?

More than that, why weren't people a real part of the world? Why didn'tthey show more honest-to-God response? When you slept with a woman,why was it something you had and she didn't? Why, when you went to aprize fight, were the bruisers only so much meat, and the crowd a lotof little screaming popinjays? Why was a war nothing but blather andblowup and bother? Why'd everybody have to go through their whole livesso dead, doing everything so methodical and prissy like a Sunday Schoolpicnic or an orphan's parade?

And then, when I was reading one of the science books, it came to me.The answer was all there, printed out plain to see only nobody saw it.It was just this: Nobody was really alive.

Back of other people's foreheads there weren't any real thoughts orminds, or love or fear, to explain things. The whole universe—starsand men and dirt and worms and atoms, the whole shooting match—wasjust one great big engine. It didn't take mind or life or anything elseto run the engine. It just ran.

Now one thing about science. It doesn't lie. Those men who wrote thosescience books that showed me the answer, they had no more minds thananybody else. Just darkness in their brains, but because they weremachines built to use science, they couldn't help but get the rightanswers. They were like the electric brains they've got now, but h