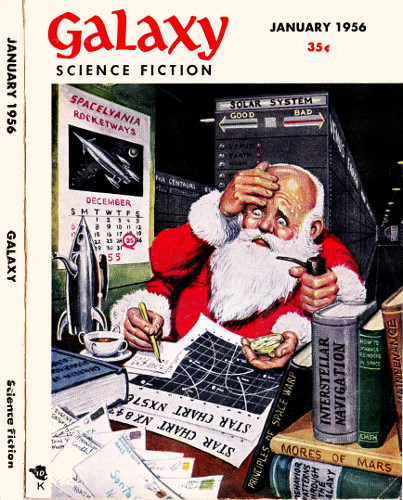

The Snare

By RICHARD R. SMITH

Illustrated by WEISS

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Galaxy January 1956.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright

on this publication was renewed.]

It's easy to find a solution when there is one—the trick is to do itif there is none!

I glanced at the path we had made across the Mare Serenitatis. TheLatin translated as "the Sea of Serenity." It was well named because,as far as the eye could see in every direction, there was a smoothlayer of pumice that resembled the surface of a calm sea. Scatteredacross the quiet sea of virgin Moon dust were occasional islandsof rock that jutted abruptly toward the infinity of stars above.Considering everything, our surroundings conveyed a sense of serenitylike none I had ever felt.

Our bounding path across the level expanse was clearly marked. Becauseof the light gravity, we had leaped high into the air with each stepand every time we struck the ground, the impact had raised a cloud ofdustlike pumice. Now the clouds of dust were slowly settling in thelight gravity.

Above us, the stars were cold, motionless and crystal-clear.Indifferently, they sprayed a faint light on our surroundings ... adim glow that was hardly sufficient for normal vision and was too weakto be reflected toward Earth.

We turned our head-lamps on the strange object before us. Five beamsof light illuminated the smooth shape that protruded from the Moon'ssurface.

The incongruity was so awesome that for several minutes, we remainedmotionless and quiet. Miller broke the silence with his quaveringvoice, "Strange someone didn't notice it before."

Strange? The object rose a quarter of a mile above us, a huge, curvinghulk of smooth metal. It was featureless and yet conveyed a senseof alienness. It was alien and yet it wasn't a natural formation.Something had made the thing, whatever it was. But was it strange thatit hadn't been noticed before? Men had lived on the Moon for over ayear, but the Moon was vast and the Mare Serenitatis covered threehundred and forty thousand square miles.

"What is it?" Marie asked breathlessly.

Her husband grunted his bafflement. "Who knows? But see how it curves?If it's a perfect sphere, it must be at least two miles in diameter!"

"If it's a perfect sphere," Miller suggested, "most of it must bebeneath the Moon's surface."

"Maybe it isn't a sphere," my wife said. "Maybe this is all of it."

"Let's call Lunar City and tell the authorities about it." I reachedfor the radio controls on my suit.

Kane grabbed my arm. "No. Let's find out whatever we can by ourselves.If we tell the authorities, they'll order us to leave it alone. If wediscover something really important, we'll be famous!"

I lowered my arm. His outburst seemed faintly childish to me. And yetit carried a good measure of common sense. If we discovered proof ofan alien race, we would indeed be famous. The more we discovered forourselves, the more famous we'd be. Fame was practically a synonym forprestige and wealth.

"All right," I conceded.

Miller stepped forward, moving slowly in the bulk of his spacesuit.Deliberately, he removed a small torch from his side and pressed thebrilliant flame against the metal.

A few minutes later, the elderly mineralogist gave his opinion: "It'ssteel ... made thousands of years ago."

Someone gasped over the intercom, "Thousands of years! But wouldn't itbe in